I’m fortunate that I got a high school education in a US public school system built during a period of post-WW2 abundance — when we invested in the future.

I feel doubly fortunate that I attended NYU when a college education was seen as a universal good.

I remember that post-9/11 politics in the US was dark. If you think about it, 2001 was 9/11 and 2008-2009 was the Great Financial Crisis. With the Iraq War in between (and after). That was a dark period for the US.

And yet, when I look back at that time, I was at my most idealistic.

One way I could remain idealistic is that the US, for all its problems, maintained two great principles:

- individual freedom — the right to make one’s own decisions

- free speech — the right to speak freely, especially to dissent

Both of these are supercharged by education.

The way I see it, these rights are fundamental. Whether you’re a politician, a government agency head, a corporate executive, a wealthy bigwig, or just any old fellow citizen, if you try to suppress my individual freedom and my free speech, you are out of line.

And I feel strongly about the converse, as well. Which is that the best of our politicians, our government agency heads, our corporate executives, they try to encourage individual freedom and encourage free speech.

That means encouraging those around you to speak out their mind.

This does lead to one tension that has to be resolved. How to handle the people who use their individual freedom and free speech rights to try to suppress the individual freedom and free speech rights of others? The answer, here, is pretty clear, to me. That’s out of line, too.

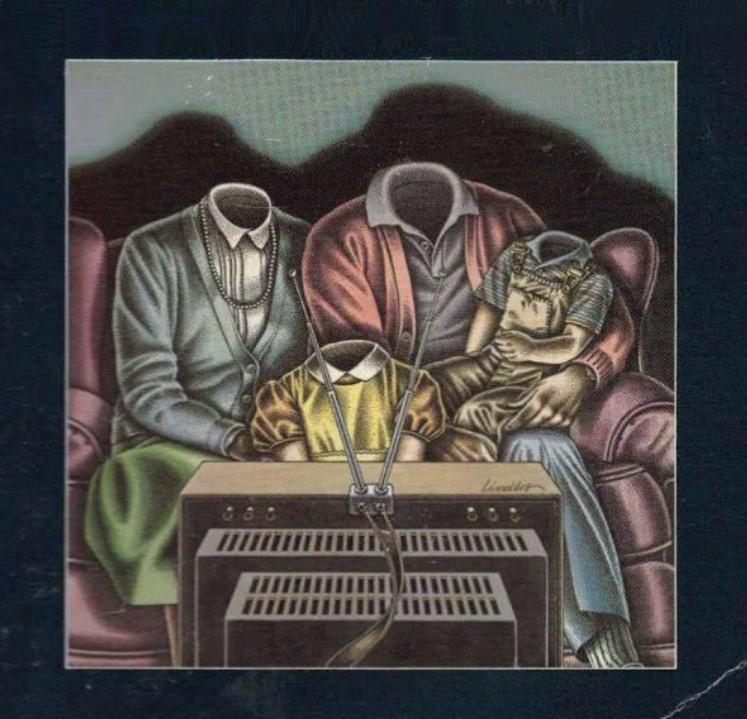

Hypernormalization is a term that refers to a strange feeling that every institution is failing, yet life goes on. This is how I felt after 9/11 and the Great Financial Crisis. It’s also how I feel now. Idealism was needed then. And it’s needed now.