When you type an address into your web browser and are brought to a web server, a lot of decentralized magic happens within the span of a few seconds. Through the web, we have an infinite media available to us.

It as though you have a beautifully-maintained bookshelf and run your finger along the spines of the books, and then pluck out the one you want. But the sci-fi part, which is more science than fiction today, is that the bookshelf has millions of virtual entries and the information you want is delivered to you instantaneously. Once this virtual book is delivered (once a website is loaded), it can be frequently refreshed with real-time updates, and it exists in a form that can be navigated, searched, read, spoken, heard, shared, saved-for-later, or even automatically analyzed and summarized.

This is a lot of power for each individual to wield.

That is a lot of text to choose from, with which you can train your brain.

And that is even if you put aside the world of paid digital books via Amazon’s empire of Kindle. By the way, this Amazon empire need not cost money to you in the US, as you can often gain (adequate) free access to it via your local library on the Libby app.

So, one thing is for sure: there are a lot of words to choose from when deciding what to read. But this also means that an individual faces a paradox of choice when they click into that blank address bar in their browser.

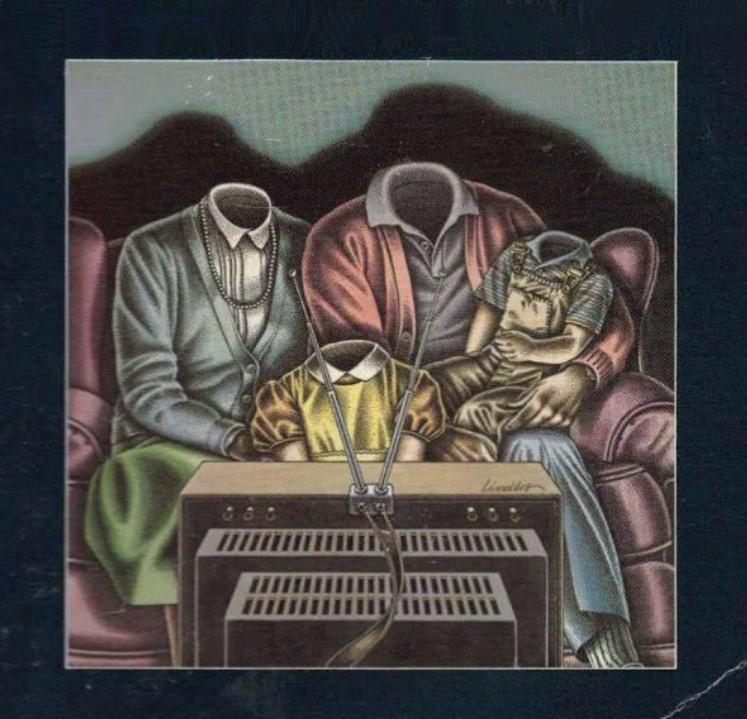

Will they, like so many others, ignore the address bar and the browser altogether? That is, despite having the “infinite bookshelf” at their fingertips, will they, instead, hit an app shortcut to one of the major passive content delivery platforms, like Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, or TikTok?

Recent research from Pew suggests that major passive-consumption mobile apps are used by a majority of Americans, and, what’s more, that usage of the most video-forward of these (YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok) is nearly universal among people 18-29 years old. As for teens, 9 out of 10 of them are online (presumably via smartphones) every single day, and nearly 5 out of 10 are online “almost constantly.” This comes from a 2023 report.

If you read between the lines of these two reports, what comes into a focus is a culture of individuals addicted to video streaming devices in their pocket, filling inevitable moments of boredom with hastily- and cheaply-produced sights and sounds, rather than retreating to the world of written words. And, unsurprisingly, people are reading less.

On the sustained slide in reading, charts and data:

America is in a reading recession:

The number of people who read on any given day has been falling since 2004. pic.twitter.com/tEYxm1bRJO

— Alex & Books 📚 (@AlexAndBooks_) January 15, 2024

These two articles have many of the source charts and graphs. (Though, sadly, they are behind a subscriber paywall; the paid-only access to many well-written words and analysis might be an interesting topic for a future post.)

I don’t judge people for settling for video, though. Our lives are filled with dull moments, and for nearly a century now, modern human society has filled those dull moments with passively-consumed media. In the second half of the 20th century, it was radio and TV. In this first half of the 21st century, it seems to be short-form video and streaming TV/movies.

But, I’m going to go against the grain and make the case for words today. I’m not going to suggest you abandon the internet, digital detox, or adopt retro tech. Instead, I’m going to encourage you to embrace the internet, but put your media on a very specific diet. Focused on one macro-nutrient: well-written words. You’re still going to eat three times a day, but you’re going to change the nutritional content of what you eat.

It’s going to be hard for me to prove that well-written words are “healthier” for you than passively-consumed sights and sounds. I don’t think there’s any research about this which could be convincing. Instead, we’re going to reason it out from first principles.

Why are words a good way of understanding the world? The first is that words represent a synthesis of ideas without an attempt at representing those ideas in your mind.

This is true even when the words are simple and direct. If you read the sentence, “Bombs fell on Romania today”, you would immediately ask some important questions. First, is this sentence true? Second, who wrote this sentence? Third, can I cross-check this sentence somehow? You needn’t even read the article attached to such an opening sentence to ask these three questions — immediately, you could be engaged in a kind of critical reading.

(By the way, here are the answers to those questions: (1) It is not true. (2) I wrote the sentence, and the reason I picked “Romania” for this example is because I have Romanian origin in my ancestry and thought it was a name-recognizable country that hasn’t been bombed by any country since WW2. (3) Having good instincts about the online media and world history, you could recognize that Romania is a NATO country; as a result, this would be front-page news for major US & EU newspapers, and this would be true regardless of coverage from English-language newspapers inside Romania, of which there are few.)

Now compare this to seeing a video that portrays bombs falling on some foreign place. You witness chaos and commotion and explosions, these are directly portrayed, and there is a clearly-spoken narration: “Bombs fell on Romania today!” The first thing that would happen upon viewing this slice of video is an emotional reaction. Your brain is basically saying, “If that is true, I just witnessed death and destruction in Romania.” But, what’s more, even if the narration is not true, somehow, you did witness death and destruction, somewhere. The facts surrounding the image may be wrong, but the feeling elicited by the image is still there.

If this video is just a 15-second or 30-second clip in a stream of clips, you likely don’t have time to ask those 3 questions before you are shuttled to the next recommended video. But, there’s a deeper problem. It’s not obvious how to answer those questions, whether using your skeptical human brain, or using some form of automation (e.g. automated parsing of other text sources). Determining whether a video is true is a hard problem, and everyday internet users have almost no way to verify a video or its source. At least, with written words, there is a web of trust: what domain/site am I at? What author wrote this? What other things has this site or author published? Can I trust them not to publish false information? And, there’s a path — still unsolved, but tractable — to allowing programmed tools to help us with these cross-check tasks.

(Indeed, the creator of Google News wrote an outline which serves as a nice starting point for how to solve this problem, and it is very readable, even if you’re not a programmer. Plus, the approaches he described are even easier today due to the success of some natural language text processing algorithms.)

What’s more, because most internet video is consumed on the top-three platforms (YouTube, TikTok, Instagram) whereas internet text exists in hundreds or thousands of independently-run major websites, our tools for cross-checking aren’t as strong as they are with text.

If you were consuming these videos in your browser, your domain would always be one of youtube.com, instagram.com, tiktok.com, regardless of the video author. But, of course, you don’t even think about the concept of a site or domain when using these services. Because you’re primarily in a full-screen mobile app. So even opening a browser to cross-check a video you just saw is asking a lot.

Put another way, we are leaving the cross-checking to the platform video hosts themselves, and those platforms are mostly ignoring that responsibility. What’s more, even if they embraced this responsibility, there is no way they’d be able to keep up: command-and-control in video media would fail in just the same way it does in the broader economy. We don’t need three well-informed central censors. We need hundreds of millions — ultimately billions — of well-informed skeptic readers.

Why are skeptics attracted to words over video? Because by some stroke of evolutionary luck, our brains have evolved to get better and better at parsing, analyzing, and interpreting words as you put it to better practice at the task. Thus, the best readers seek out the best writers, and words written by humans who view it as their life’s work to write words are often the best writers (or, at least, readable writers). What’s more, professional writers have a reputation to maintain, thus their words are often of higher quality (though not always). Professional writers are also read by thousands (or millions) of skeptical readers, who serve as an effective check on their excesses.

Carefully chosen and edited words, but also fearlessly written words. That’s what your diet could benefit from. That is the best communication tool humanity has to offer us today.

Text was super-charged by the internet of the 1990s and early 2000s, and supercharged again by the high-speed and mobile internet of the 2010s. We can find more of it, more quickly, than ever before. Our ability to work with text also looks like it’s going to be revolutionized once more in the 2020s by the rise of LLMs. And yet, much of our society is moving toward passively-consumed video in their media diet. What a waste of an opportunity!

(On LLMs, what are my hopes for them in the world of text? Well, there has been much hand-wringing about LLMs commodifying copy writing tasks, and perhaps replacing journalists with AI journalists. But, I am not talking about an LLMs ability to write fluent text, which, I agree, has its risks. I am talking about its ability to read, parse, and analyze fluent text, and answer fluent natural language questions about that text, perhaps also helped along by world knowledge from sources like Wikipedia. In that role, it is pure utility, with hardly any downsides. In the example I gave above, “Bombs fell on Romania today,” I could imagine an LLM helping me answer questions like, “Does Romania have any major allies pledged to its defense?” and “Does Romania have any English-language newspapers?” Even ChatGPT4 answers these questions adequately today. But in the context of reading such a piece of “breaking news,” both of these questions, answered by an LLM in the context of the article, could help read such an article more skeptically and cross-check its claims in a snap. One of the best live demos of such a use case comes from Google with their NotebookLM tool, described by the Google team behind it here.)

It’s worth reflecting on the fact that in many countries — China, Russia, North Korea, just to pick three — most of the English-language words that are available to you in the US, EU, Canada, and Australia via the internet (and further through the Amazon Kindle empire of paid books) are not even allowed to be published and read. What a gift you live with everyday that millions living in those countries would pay a handsome price to access.

Broadly, in the free-speech-oriented modern democratic societies, we not only allow a mass of free words to be published, but also openly discussed and debated, even when those words are directly critical of government officials, corporate executives, and other members of the propaganda class. You now have better tools at your disposal to put critical reading into practice than at any other time in history. What will you do with this privilege and responsibility? I think you’ll now start to recognize that there are better answers than: “watch a reel.”

Acknowledgements, and how to find specific sources: Thank you to Adam for reviewing a draft of this essay. One comment he had is that he wished I had shared my specific text media diet. I can understand the request, but I felt it wouldn’t be appropriate in this post for me to pick specific sources to recommend. A couple of nice places to start, though, would be to look at the AllSides Media Bias Ratings and the Wikipedia page on the largest US newspapers by circulation. Print newspapers may be in decline, but the biggest among them have robust digital editions and paid subscription programs. For long-form content that is less newsy and more in the realm of special interests and cultural analysis, take a look at the Apple News+ Publication List, as Apple tries to curate long-format “magazine-style” content for its popular paid news app for iPhone and iPad users. The goal is to seek out slow journalism.

My personal approach is to prefer print books to all other reading, settle for ebooks (via Kindle app) for some reading, mix in some audiobooks via Audible, and then, for the daily fix of news and analysis, try to stay at the headline and news cluster level, and only go deeper than that very intentionally, preferring long-form writing and analysis to quick takes. Google News and TechMeme are reasonable ways to scan headlines from multiple sources. Instapaper is a reasonable way to be more intentional about which pieces to read (or discard) via its browser plugins and mobile apps. As might be expected given that I wrote this post, I avoid all short-form video in every app (no “Watch” tab in Facebook, skip over “Reels” in Instagram, ignore “Shorts” in YouTube). I don’t use TikTok whatsoever. And as for anything resembling cable TV news, I instinctively downvote, mute, or skip.

4 thoughts on “Putting Your Media on a Diet”