Note from the future: this post written in November 2016. A lot has happened to Twitter (or, Twitter/X) since then. But, the fundamental analysis of Twitter’s growth dynamics outlined in this post continues to hold true even 8+ years later.

Twitter is the public Internet company everyone loves to hate these days. It’s not growing. No one wants to buy it. And people are genuinely confused: what, exactly, is Twitter? Is it a social network? A “micro-blogging” platform? A “live events destination”? A social data company?

I am one of Twitter’s active users, tweeting on topics such as analytics, Python programming, and the media industry, in which I work. In my day-to-day dealings with journalists, editors, social media managers, audience development folks, and others in the media industry, it’s clear Twitter has a special position among the professional class of media raconteurs.

There’s a sense that Twitter is the “global heartbeat” of the Internet’s consciousness in a way that considered professional media outlets, Facebook, and Google are not. Journalists use Twitter as a place to find news, a place to break news, and a place to monitor news as it evolves. It’s great for these use cases. But it’s frustrating to these same journalists to learn that Twitter only drives a fraction of the traffic to their sites that Facebook does. So, what’s going on? Why isn’t everyone using Twitter?

Positioning Twitter against ‘the competition’

Google is an index of the web’s public content (which includes Twitter, but excludes Facebook). No one “posts stuff to Google”. You “find stuff on Google”. And finding stuff is certainly one of the primary daily activities of the web’s global user base.

Facebook is a feed of your own personal content, intermixed with some of your own semi-public content and the private and semi-public content of you, your friends, colleagues, and peers. You don’t “find stuff” on Facebook — you “discover” stuff, instead. Its never-ending feed is trying to showcase that which might engage your brain, however slightly, and then engage your arm, and your mouse, for the occasional click of the ‘Like’ button.

Twitter, by contrast, is a site where almost all of the content is public, where every piece of content has a URL (or two), and where there are three distinct kinds of Twitter users: anonymous searchers, subscribers, and creators.

In this respect, Twitter actually shares a lot more in common with Wikipedia, as an organization, than it does with Facebook or Google. It relies on a small group of active users (the creators) to make a network of content that attracts a larger network of readers (subscribers, searchers). One important difference with Wikipedia is that it is run as a for-profit company, rather than as a non-profit foundation.

Anonymous searchers, subscribers, and creators

What are the behaviors of these three groups — what are they getting out of the Twitter experience?

Let’s start with anonymous searchers. Twitter has a full index search, of which it is very proud. But I suspect, it gets relatively little traffic. The only exception is during big Internet-wide cultural phenomenons; a good example is the “Blood Supermoon”, which even earned a special emoji’ed hashtag at Twitter.

If you’re already a Twitter user, it’s worth trying to experience this for yourself by going to Twitter.com in an incognito window. In this mode, Twitter looks a little bit like Google News. It’s trying to help users answer the question, “What’s happening right now?” Searching and digging through topics (which Twitter now calls “Moments”) are pretty much all an anonymous user can do.

The big problem with Twitter’s anonymous searchers is that they are using Twitter for a pretty niche use case. People are already trained to go to Google to search for stuff happening right now. Though Twitter gives a slightly different view, it’s also a narrow view.

For example, on election day in the US this year, many people will search Google for the exact search phrase. “election day”. Some of these people will be looking for news; others will be looking for information on how to vote; others will be looking for early exit poll results. Google will serve all of these searchers equally well. But if someone goes to Twitter and searches for the same, all they will see is raw live commentary about the election — probably mostly from news publishers and the candidates themselves. This might be interesting to some (e.g. journalists) but not to the wider public. And Twitter will especially fail at any utility searches, such as finding your local polling information.

So, anonymous searching is a use case poorly positioned against Google. Let’s look at the other two Twitter use cases: creating content and subscribing to content feeds. These are Twitter’s most compelling use cases, and the bread and butter of the service. But, they, too, are problematic when compared against Facebook.

Let’s start with subscribers (the bigger group). If a user signs up for Twitter, they are encouraged to follow three kinds of accounts: celebrities/brands (“power users”), interesting people (“active users”) and their own personal friends (“other subscribers”). I suspect many Twitter users don’t follow many of their personal friends, except perhaps if those friends are also work colleagues of sorts. This is because Facebook already serves the purpose of a “verified social network”. So, instead, the focus is on subscribing to interesting people and celebrities/brands, such as news publishers, companies, or people whom you don’t know personally, but whom you respect professionally.

Examples of “interesting people” for me would be Raymond Hettinger, a core Python developer, and Edward Tufte, an information design expert. I’ve actually met each of these people (briefly) at conferences/events, but I wouldn’t call them friends. Following them on Twitter allows me to keep up with their thoughts and updates. Examples of “celebrities/brands” for me might be Elon Musk and NASA. Like most geeks, I like outer space, and I like to watch videos of rocket launches.

In this respect, Twitter actually operates as a lightweight replacement for RSS/Atom and the informal blog networks of the early 2000’s. And it’s a good one: even the creator of RSS likes it. (It’s proprietary rather than open, but that is another matter entirely.)

Viewed this way, Twitter is, for many users, actually a way to follow people and brands you think are important. Twitter simply feels right for this use case. For example, this 2012 post where President Barack Obama publicly celebrated his winning a second term in office with an iconic photograph of him embracing his wife, posted directly to his official Twitter account on the evening of victory:

Facebook competes among well-known people and brands, too: in 2007, it launched “Pages”, which, from their original marketing material, “allows users to interact and affiliate with businesses and organizations in the same way they interact with other Facebook user profiles.” And Facebook Pages have huge adoption: many small businesses use them in lieu of websites; many news publishers use them as a primary news distribution channel; and many celebrities have them, as well.

Let’s now move to the last group: creators. This is Twitter’s most important asset. They are the content creators for the entire network: the people who keep the thing running.

Public lives and private lives

Here’s an interesting question: why do people bother posting to Twitter at all? Given the existence of Facebook Pages for over 9 years, and given that Facebook’s overall audience is an order of magnitude larger than Twitter’s. How does Twitter even have a user base who’s willing to put content online through its smaller distribution channel? The answer, I think, centers around the notion of an individual’s public life and their private life.

I’ll speak from experience: my own life. In my “public life”, I am the co-founder and CTO of a data/analytics company, Parse.ly. I am a programmer, Pythonista, tech enthusiast, media analyst, and conference speaker.

But in my “private life”, I’m just Andrew — a guy who works from home in Charlottesville, VA; who likes to play with his labradoodle, Kevin; who recently spent a month in Southern Spain with family and friends.

The people who follow me looking for new dispatches from the land of data and analytics probably don’t also want to hear about my adventures training my puppy, or see random photographs of me on random vacations.

It’s true that to reflect this in social media, I could have my “private life” on Facebook as my verified profile, and then live my “public life”, also on Facebook, as a “Page” representing my public persona. But this just feels weird. As a result, over time, I have made my Twitter account reflect my “public persona”, whereas my Facebook account could still be used to connect with old friends and acquaintances.

And here, I think, is where Twitter’s “growth problem” comes from. It has established a competitive niche (a reason for creators to have an account) only due to a quirk around how awkward it is to lead a public and private life in parallel on Facebook. For example: I can end a technical conference talk I give by saying, “Follow me on Twitter at @amontalenti.” And this makes sense. But if I end the same talk saying, “Follow me on Facebook”, I am inviting hundreds or thousands of strangers to awkwardly send me Facebook friend invites that will be unrequited.

Following someone is not the same thing as knowing someone, and Twitter has managed to own the behavior of interested parties subscribing to the updates of relevant and interesting people who share those updates. Facebook, by contrast, is the “verified” social network of record. For many people, being “friends” on Facebook means that you at least know the person, in some personal sense.

Here’s the rub: billions of people lead private lives, but only millions lead public ones. This means that Facebook’s total addressable market for content creators is every connected human on the planet (everyone has an interesting photo to share); whereas Twitter’s addressable market for content creators are only those who have “followings” outside of their private lives (e.g. those who write, speak, perform, or do something else worth sharing publicly).

This is a tiny fraction of the global population. This is Twitter’s growth problem, in a nutshell. It’s the Internet’s 1% rule, all over again.

In Internet culture, the 1% rule is a rule of thumb pertaining to participation in an Internet community, stating that only 1% of the users of a website actively create new content, while the other 99% of the participants only lurk.

Hacking around the 1% rule

How does Google hack around the 1% rule? It indexes the entire web.

It’s true that most people don’t run websites, but when you index every website across the entire Internet, you have enough searchable content that the 99% (anonymous searchers) are completely satisfied with what they find.

How does Facebook hack the 1% rule? It found a middle ground between “creators” and “subscribers”, which one might call “private sharers”.

Though not everyone is willing to permanently and publicly post their thoughts, photographs, or goings-on online, everyone who leads a private life (which is to say, everyone) is willing to share thoughts, photographs, or goings-on with actual friends. In short: when the friction of sharing is lowered and true (small group) privacy is enforced, you’ll turn subscribers into creators.

You might now ask: how can Twitter hack 1% rule? That’s the problem. I don’t think it can. I think it’s an essential problem for the service. If Twitter is a public content stream, then its creators will always be a (relatively) small group of public creators, and thus the content that Twitter exposes to the 99% of anonymous searchers or subscribers will be limited to that small group’s output. This, in turn, will keep the size of the network limited.

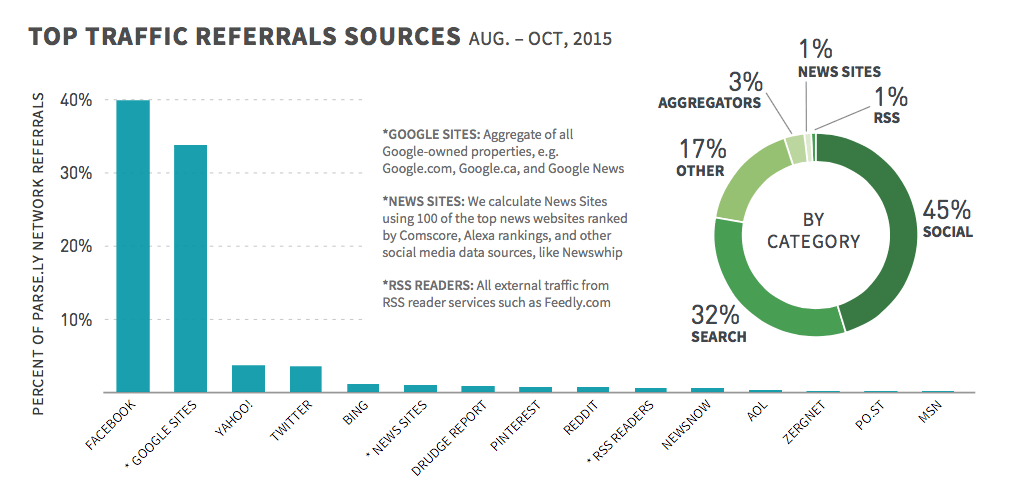

At Parse.ly, my team studies Internet trends around news data, and have for several years been ranking Internet sites by the amount of traffic they send to news publishers. Despite Twitter’s popularity among journalists, it’s still a small fraction of referral traffic when measured up against Facebook and Google. The root explanation here isn’t any usability or technology problem: it’s simply the small overall size of Twitter’s network of active users alongside these two giants.

To put it another way: if Facebook were to buy Twitter, it would likely operate it exactly as it operates Instagram and WhatsApp. As a separate brand, targeted to a separate user and a separate use case. Twitter would be what semi-public and very-public figures use to talk to their followers and fans. Facebook would remain the service tied to every individual’s private identity.

Hundreds of millions of DAUs isn’t so bad

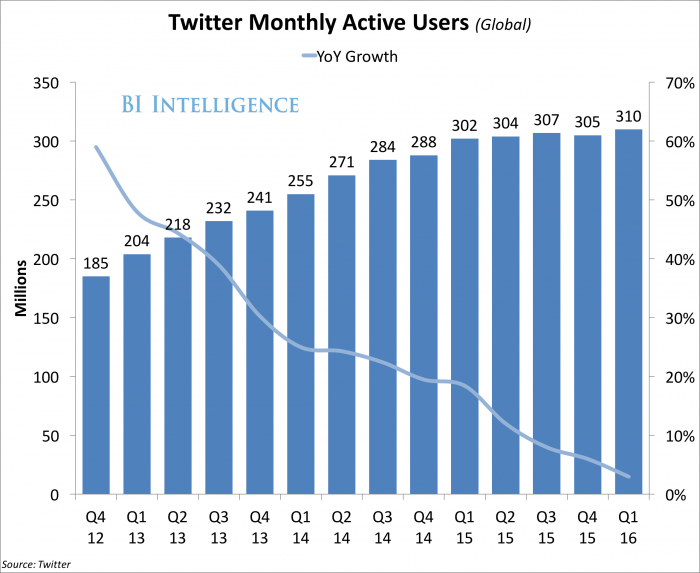

Twitter has plateaued at around 300M daily active users. That is a lot of people. I work with multi-billion-dollar media companies every day who would love to have a consumer web/mobile property with that kind of user activity. The service has a great user experience for creators and solves a real problem. But, it can’t be as big at Facebook or Google. It just can’t.

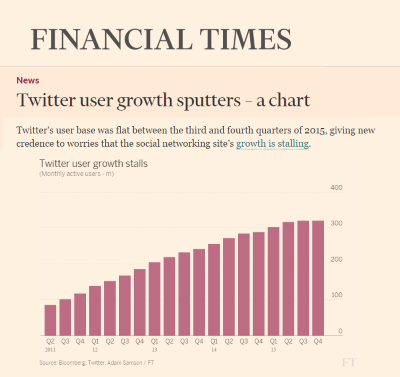

Business Insider charted Twitter MAUs and growth, and as you can see, user growth isn’t just stalling in 2016 — it’s practically 0%.

I think this presents a conundrum, both for Twitter management, and also for us as Internet users. Do we need every service we use to achieve mega-scale? Or can we live with a service that makes real money, solves real problems, but simply doesn’t have the network model to grow to be a part of every single Internet user’s limited attention span? (Note from the future: This linked blog post also inspired a popular 2020 Netflix documentary/polemic, The Social Dilemma.)

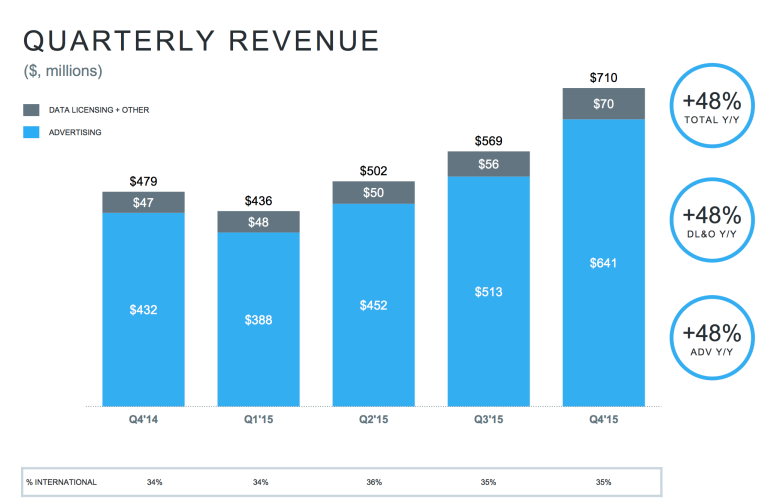

Because remember, for all the criticism of Twitter’s stalled user growth, it’s actually a terrific business. It generates billions of dollars in advertising revenue, as well as hundreds of millions in data licensing revenue, per year:

The issue isn’t with Twitter, per se, but with the expectation that every public Internet company needs to strive to be “the next Facebook”. But there can only be one — or maybe two or three — dominant consumer attention companies. Twitter shouldn’t try to be the next Facebook; even if Facebook bought Twitter, it wouldn’t try to make it the next Facebook.

Is a billion-dollar company used by a significant fraction of Internet users that solves real problems on the web enough? It should be — but it seems like it isn’t. That’s a serious problem for our current growth-obsessed mindset for public Internet companies.

Wikipedia, StackOverflow, Reddit, the NYTimes, and other top-100 sites each generate unique value for the web ecosystem, and Internet communities agglomerate around these major destinations, seemingly following Zipf’s Law.

So, whether Twitter is able to survive as a public Internet company is actually a larger story about whether we are able to have sustainable Internet companies with millions of daily users, rather than billions.

If we can’t figure out how to operate useful companies like this profitably and in perpetuity, it’s a severe threat to the web overall.

Coda from the future: In my concluding remarks of this 2016 post, I said, “whether Twitter is able to survive as a public Internet company is actually a larger story about whether we are able to have sustainable Internet companies with millions of daily users, rather than billions.” Indeed, in 2022, 6 years later, Twitter was dramatically taken private by Elon Musk and experienced massive layoffs as the company was right-sized for its plateaued growth trajectory.

Musk now refers to Twitter as “X” (I refer to it as “Twitter/X”, as “X” is a tough brand for mere mortals to understand). Twitter/X continues to operate, but likely also continues to have plateaued growth dynamics, due to the essential structure described in this post. Musk’s public plans for Twitter/X, to achieve more rapid growth, is to diversify its business outside of public messages and into the worlds of private direct messaging (e.g. the space held by WhatsApp, Telegram, and Signal in today’s market), payments (e.g. Paypal, Venmo), and chatbot-based and LLM-based AI (e.g. OpenAI ChatGPT, Microsoft Copilot).

This gambit is to turn Twitter/X into an “everything app” or “super app”, much like WeChat is such an “everything app” in China. It’s hard to predict whether this gamble will work, but what is certain is that the business strategy behind it has something to do with the plateaued structural growth dynamics described in this post.

If we wanted Twitter to survive in the form it took in the 2016-2018, it probably would have needed to convert to a non-profit, like Wikipedia. In the face of Musk’s takeover of Twitter, some alternatives have sprung up outside of the corporate world, like the open source Mastodon project and the Bluesky project. (The latter is a public-benefit corporation, but also maintains some open source projects.)

These projects face stiff competition, not only from Twitter/X itself, which already has the network, but also from new entrants like Meta/Facebook’s Threads and from the general decline of reading as an internet pastime.

As for me, I’ve put Twitter/X in a box for my personal usage, pretty much the same box I described in this post back in 2016. That is, I use it to publicly post as my professional persona and to keep up with professional acquaintances that I “know of,” but whom I don’t personally know as friends. I also use it to follow individual journalists and writers whom I trust, to whatever extent they are still posting there.

One thought on “The Twitter growth conundrum”