Edward Tufte is the father of modern information visualization. If you don’t know who he is, you probably should, and you can get up to speed by reading this profile in Washington Monthly, The Information Sage.

Last year, I attended one of Tufte’s one-day courses in NYC. I even showed him an early, prototype version of Parse.ly Dash. His feedback — even if it came quickly in 5 minutes — was helpful in understanding how to move the product forward.

I thought, when attending his presentation, that my main takeaways would be in the field I associated with him, namely, information visualization. But actually, my main takeaways were about communication, teaching, and journalism.

Communication

Tufte is an eloquent speaker who chooses his words carefully. He realizes that each medium has a capacity to communicate an idea. His spoken words are about intimacy and impact. His written words are about elaboration and illumination. His accompanying graphics are moments for reflection and self-motivated information discovery.

In short, watching him teach a course is to realize how anemic many of us are with regard to communication. Tufte views the tools of communication as having different strengths and weaknesses. Too often, modern professionals have problems combining these tools effectively. For example, limiting ourselves to spoken word (phone calls), written word without graphics (e-mail), and summary lists (project management tools).

In our distributed team and engineering-oriented culture at Parse.ly, we often talk about code-as-communication. We try to communicate with actual code — whether fully functional, prototyped, or stubbed — since this often best communicates software ideas with more density and clarity than an auxiliary artifact. But one can’t use code to communicate design considerations, process/workflow, or strategy; for these, we must resort to more universal forms of communication.

Take note: no matter how anemic and limited our communication approaches end up being, outside of a corporate setting, no one ever thinks to communicate via PowerPoint. I don’t give my family an update in a slide deck. I don’t tell my girlfriend how my day went in bullet points. This should already tell us that there is something wrong with that particular medium.

Teaching

Tufte views teaching as effective communication with an aim to inform and cause reflection on the part of the student.

PowerPoint is, in Tufte’s words, “pushy”. It “sets up a dominance relationship between speaker and audience, as the speaker makes power point with heirarchical bullets to passive followers. Such aggressive, stereotyped, over-managed presentations[…] are characteristic of hegemonic systems…”

By contrast, teachers “seek to explain something with credibility”. He goes on, “the core ideas of teaching — explanation, reasoning, finding things out, questioning, content, evidence, credible authority not patronizing authoritarianism — are contrary to the cognitive style of PowerPoint, and the ethical values of teachers differ from those engaged in marketing.” (Read more in his Metaphors for Presentations.)

Journalism

Tufte draws many of his goals from the ideals of journalism, especially print journalism. A well-written news article has a certain structure, style, and presentation priority (see e.g. the inverted pyramid and AP Stylebook). The frontpages of newspapers are made for scanning and are densely packed with headlines, text, and images. The printed pages of magazines combine text, images, charts, tables, and graphs as necessary, and use color and size to draw attention to one area or another.

He is especially fond of scientific journals and magazines, such as Nature. I believe his respect for these media organizations above others comes from the unique challenge they face: to take something inherently complex — such as a scientific discovery or result of research — and present it to an audience who might have limited understanding. These organizations also operate under the constraint of limited space — often devoting only a single page to a complex topic. Tufte’s point, here, is that if the journalists at Nature can condense an important scientific discovery into a page of information and have it still be readable and comprehensible, then you have no excuse for giving one-hour-long PowerPoint presentations that convey nothing of substance.

PowerPoint at NASA

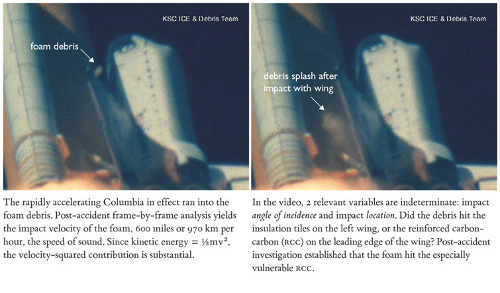

The height of Tufte’s contempt for PowerPoint probably came when he was asked by NASA to review the cause of the Columbia Shuttle Disaster from the point-of-view of a corporate communication failure.

In his scathing report, “PowerPoint does Rocket Science”, Tufte takes apart the PowerPoint presentations that were made by Boeing engineers to NASA management when assessing the damage caused by the foam debris detected at launch. In it, he writes:

In the reports, every single text-slide uses bullet-outlines with 4 to 6 levels of hierarchy. Then another multi-level list, another bureacracy of bullets, starts afresh from a new slide. How is it that each elaborate architecture of thought always fits exactly on one slide? The rigid slide-by-slide hierarchies, indifferent to content, slice and dice the evidence into arbitrary compartments, producing an anti-narrative with choppy continuity. Medieval in its preoccupation with hirarchical distinctions, the PowerPoint format signals every bullet’s status in 4 or 5 different simultaneous ways: by the order in sequence, extent of indent, size of bullet, style of bullet, and size of type associated with the various bullets. This is a lot of insecure format for a simple engineering problem.

It is worth reading every word of Tufte’s analysis.

In erecting an edifice of bureaucratic corporate communication around the simple technical content of the problem at hand, NASA managers and engineers managed to bury the lede: that their safety models were insufficient to predict with confidence the integrity of the shuttle and that there remained serious doubts among engineers of the shuttle’s overall safety.

So, the next time you are thinking about giving a PowerPoint presentation, you may want to ask yourself: Is this the best way I can communicate my ideas? Is this how I would want this material taught to me? How would a journalist elaborate my ideas when presenting them to the public?

my comment kinda got out of hand, so i ended up writing a reply in g+. Here it is:

https://plus.google.com/101108572327786417785/posts/R4Vrq89v2P5