My first mobile device was a Palm V. I understood the power of mobile really early. I was 15 in 1999, when the Palm V was released. I first came across the Palm devices in 1998, when the Palm III came onto the scene. I never owned one, but played with the one my Dad owned, but barely used.

This device was comically under-powered in retrospect. It had 2 megabytes of RAM, which had to be used as not only the working memory of the device, but also the storage. It had a 16 Hz processor, a 4-greyscale screen, and a stylus-driven interface.

The Palm V was an amazing device. In lieu of the plastic of the Palm III, it had a finished anodized aluminum finish, very similar to the kinds of sleek devices we would only begin to regularly see in the last couple of years. It was nearly half the weight of its predecessor, and as thin as the stylus you used to control it. It had a surprisingly well-designed docking station (imagine this: since USB hadn’t yet been developed, it had to sync over the low-bandwidth Serial Port available on PCs at the time).

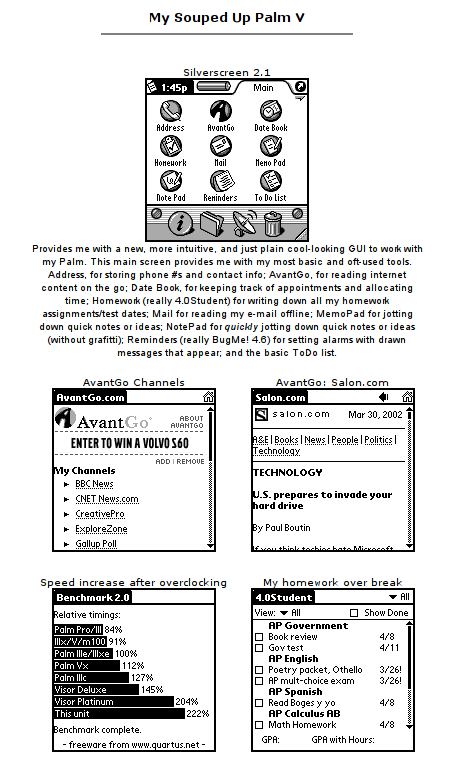

I came across a time capsule of my Palm V usage. Since I was a web designer at this time, but since it was a “pre-web” era, I often put together little static HTML websites to demonstrate features and ideas to my friends. I did one of these for my Palm V.

A Mobile Device of Pure Utility

In a world without cell data plans, wifi networks, & laptop computers, my Palm V provided much of the same utility that is now spread across these various pieces of everyday technology infrastructure, but in a single device. I kept a unified to do list of my life, and a specialized task manager specifically for coursework and classes. In it, I tracked not just homework assignments and due dates grouped by class, but also my grades — so that I could prioritize work to optimize my grades.

I think I only got my first cell phone a couple of years later — and they were nowhere near ubiquitous yet, so my contact manager was actually being used to store landline phone numbers and addresses of my friends — and likely, of local take-out / delivery restaurants.

What was AvantGo?

I sometimes tell my friends that despite the lack of infrastructure in school for it, I was indeed a “child of the Internet”. This was mostly thanks to AvantGo.

When I was at home on my personal computer, I was already an avid web content reader from early pioneers like Salon.com, CNET, Wired, and BBC. But I couldn’t easily read their content at school. AvantGo was an early, popular service for Palm devices that let you download and sync “content channels”. Of course, this is way before RSS/Atom. Channels were really mobile-optimized static HTML websites that each provider would put out daily with a snapshot of their latest content. In the screenshot above, you can see me reading an article from Salon.com dated March 30, 2002.

In addition to officially supported channels that were put out by major publishers, you could also download and sync arbitrary web content. This was essentially an early version of Readability / Instapaper — in some ways, much clunkier, in other ways, more complete. The software would go to the website and try to mobile-optimize a site (stripping it down to basic HTML), while also crawling the relative links. For example, at the time I was very interested in participating in the Debian open source project, so I had AvantGo sync the Debian Policy Manual, which contained hundreds of HTML pages full of reference information.

So, yes — when I was bored in Spanish or Math class, I’d pull up a political article from Salon.com, a tech piece about the 2000 tech bubble forming in Silicon Valley from Wired, or read over open source software development guidelines. I was a child of the Internet, and the Palm V kept me tethered in a pre-mobile world.

What makes AvantGo so interesting, upon reflection, is that despite everything against it — under-powered mobile devices, no ubiquitous wireless Internet access, and a less standardized world-wide-web, it still satisfied a use case that has yet to be satisfied today. Namely, it provided a way for me to curate the “best sources of content” I found on the web, and sync and download all their content to provide a personalized, offline library of content. Instead, we have nothing but fragmentation today — individual native apps for each news publisher, RSS readers like Newsblur providing a way to get the latest updates from a group of them, and mobile web browsers for everything else.

Many in the industry see AvantGo as the first to attempt [a shift to mobile]. AvantGo’s software pulls content from a user-defined list of sites and loads the content into the PalmPilot’s synchronization queue on a desktop computer. When the PalmPilot is synchronized with the desktop machine using 3Com’s own synchronization software, the desired content is also uploaded to the Pilot — giving users a fresh stash of data to dig through offline.

– from “The Next Browser War?”, Wired, 1999

Smartphones

Obviously, devices running iOS and Android are finally starting to make ubiquitous computing a reality, and are providing less clunky ways to access web content.

But I think it’s worth reflecting on what my Palm V had going for it nearly a decade ago that has yet to arrive in this new era.

- Vindigo: When I was a student at NYU, I had instant access to all the restaurants in New York, complete with editorial reviews, walking directions, and sometimes, menu previews. I also had a list of restaurants I had visited with notes about dishes I had ordered. This, despite my Palm V having no data connectivity, no built-in GPS, and extremely limited storage capacity. Yes, today we have tools like Yelp and Urbanspoon, but these tools are actually comparably slow and impersonal. I think there is an opportunity to win this market with speed — create an offline-synced, indexed, full restaurant database stored on the user’s phone, along with a personalized cache of restaurants that user has visited.

- 4.0 Student: There is certainly no shortage of todo list applications out there, but I have been surprised to not see a rewrite of 4.0 Student for iOS and Android. The specific functions that a task manager needs to be optimized for students: grouping of tasks by course, quick entry of due dates, ability to enter in grades for tests and assignments, and ability to estimate a current GPA in the class. This allows a student to smartly prioritize his or her coursework by those classes that most need attention. A well-designed app probably has little need for web syncing, since it could be operated entirely from the mobile device.

- AvantGo: I do think RSS/Atom and the modern news readers are an important innovation for online content. But some content doesn’t fit into the RSS/Atom spec — think Wikipedia, HTML e-books, etc. Mobile devices have plenty of space for this, and these days, they even have the compute power to do the crawling / caching themselves (without the need for a sync via desktop). There are probably a ton of interesting use cases here — think about doctors/nurses who might want an offline cache of all of Wikipedia’s medical topics; a conference attendee who might want an offline sync of the conference agenda / schedule; or a military soldier who might want to sync the Army Field Manual.

A great example of online/offline mastery that I witnessed in a mobile application is Spotify’s support for bringing an entire music playlist offline. Offers the best of both worlds.

We’re certainly living in an age of ubiquitous, wireless Internet access, whether via cell towers or wifi. But that doesn’t mean that the smartest applications are those that exclusively rely on data access being present. In fact, making your application rely on data access will almost certainly make it slower than it could be.

Due to our obsession with connectivity, I think many developers are forgetting about use cases where the mobile device is meant to be a smart accessory to our lives, rather than a portal to the web. These are no longer “thin clients” — instead, we should think of them as powerful handheld computers. Recent iPhone and Android devices feature dual-core processors at speed above 1Ghz and 1GB of RAM. In 1998, typical desktop computers were slower than this (e.g. a single-core P3 600 Mhz w/ 128MB of RAM and 10GB of disk storage).

Yes, we’ve put the power of a desktop computer into the palm of a user’s hand. But, are we really tapping this opportunity?

Brings back memories — my first mobile device was a Palm VII back in 1999. Kept it in one pocket and the slick fold-out keyboard in the other. Fellow students were very confused to see that busted out to write e-mails! It’s fascinating to reflect on how much that device had in common with the new wave of tablet and smartphones.

Oh man. When I lived in Boston around that same time, I lived and died by AvantGo. Had the same setup and drooled over folks who had a Handspring or Palm VII. Eventually I got a Treo and prompted melted it on a ski trip (long story).

I think/hope we’ll see more PWA web apps start to explore “offline”capabilities in the years ahead as folks understand what can be done with service workers/web notifications/etc., and maybe the AvantGo of 201x is not that far off…