Note: At the time of this post’s publication, I was the founder/CTO of Parse.ly, a company that worked closely with major media companies on a real-time analytics platform.

The attention economy is broken.

Brands are spending billions of dollars on a complex digital ad ecosystem to influence consumers, but with often terrible results. Publishers, meanwhile, have never had bigger digital audiences — but they only earn a fraction of the revenue, mainly due to the power of the Google/Facebook adtech dominance.

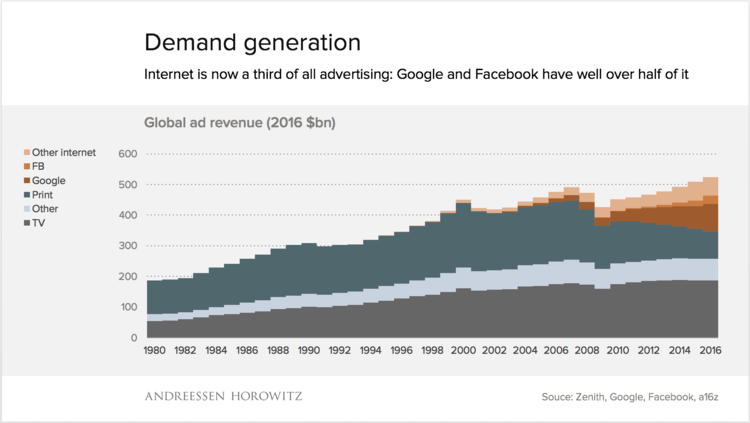

Spending on Google and Facebook ads exploded between 2010 and 2016, as shown by the orange areas above. Google and Facebook also have about half of all the advertising revenue in the Internet category. It’s very likely that by 2020, that will be closer to 60–70%, with every other Internet publisher on the planet fighting for a shrinking portion of ad dollars.

Consumers — you and me — are the ones footing the bill. We see increasingly slow page load times for publisher pages which are bloated with ad tech vendor code; increasingly invasive ads from brands who are desperate to catch a click; and, a media trend toward outrage, rather than thoughtful debate.

On this last point: it is outrage, not truth, that prevails in an Internet economy built around attention capture and auction, which is how our programmatic digital advertising ecosystem works.

This is because outrage — through a quirk of societal and brain evolution — is more effective at capturing our time. Indeed, as we’ve been learning, outrage decoupled from truth is one of the most engaging forms of content on the web.

We’ve hit rock-bottom

“Fake news” isn’t a Russian conspiracy to undermine our democracy; it is, instead, the end-state of an unhealthy race-to-the-bottom for consumer attention.

And yes, we’ve hit the bottom.

Just think through where we are now: Google perpetually records your voice, your search queries, your location, and your browser history. Facebook has enough data on you, your friends, and your personality to persuade you emotionally and politically.

Meanwhile, the rest of the web is frantically trying to catch up. That is, thousands of companies and hundreds of thousands of sites are trying to catch up to a state of complete and total digital surveillance. Even though this milestone has already been achieved — on multi-billion-user scale — by the top two players.

The first step to a solution is to admit this much: we have a problem. I think we can all agree we need to send digital advertising to rehab.

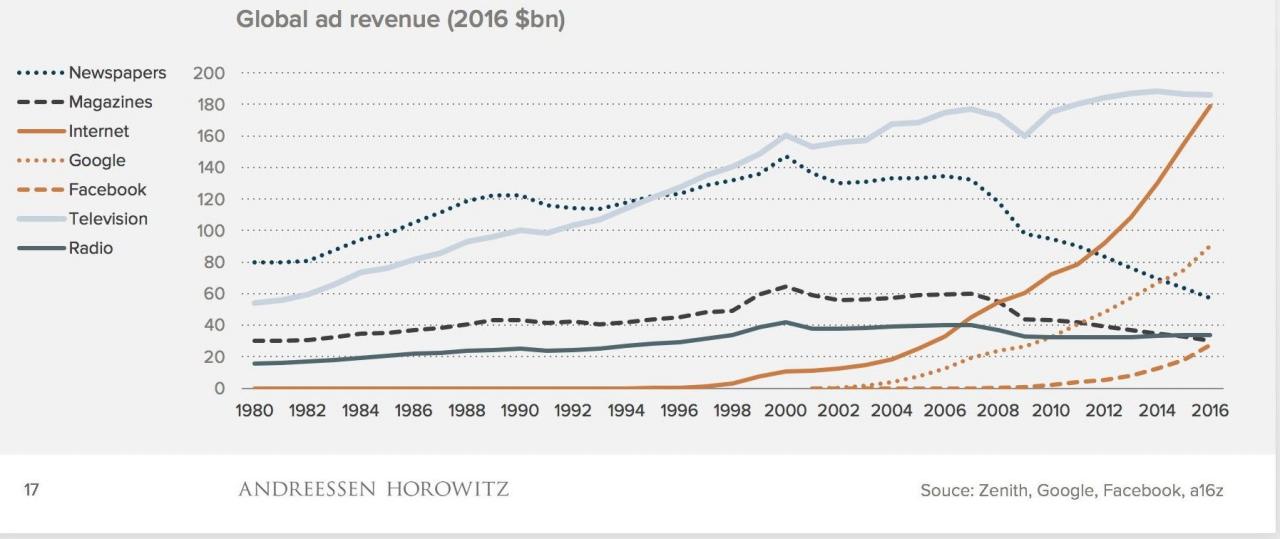

Billions at stake

It’s hard to deny the stakes: billions of dollars continue to pour into digital, displacing other forms of attention-oriented media such as radio, newspapers, and magazines. What’s more, even if consumers shift all of their attention to the Internet and TV, they still have a limited capacity for being persuaded. There are only so many hours of advertising one can be exposed to in a given day.

The important thing to recognize is that TV and Internet advertising are the only growing categories, with newspapers, radio, and magazines now in a very steady decline. But as you can see, the lion’s share of the ad spending growth is being driven by Google and Facebook alone.

Can we imagine a different system — one built on a more authentic foundation?

I think we can. The attention economy may be broken, but I think we’re rapidly approaching an inflection point, which I refer to as The Great Reckoning.

In The Great Reckoning, publishers come to a very important realization: programmatic display advertising is not the only — and certainly not the best — revenue source to sustain their business. If anything, it’s a revenue source at the margins. They will cede the big “at-scale targeting” game to Facebook, Google, and similar people-based advertising systems.

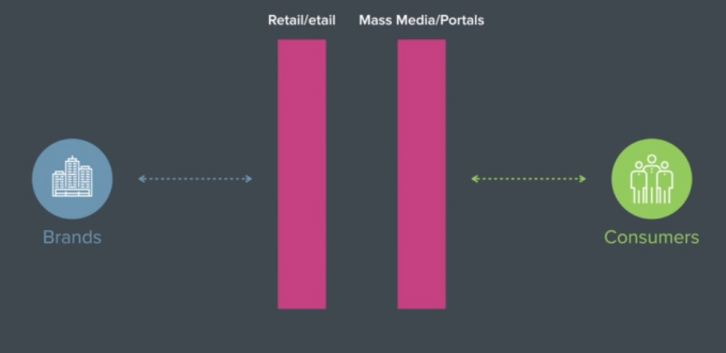

Prior to “The Great Reckoning,” brands viewed retailers and mass media as critical intermediaries for selling products and services to consumers. Retailers and mass media were “attention merchants” who essentially licensed consumer time to brands for a fee — whether that fee was an advertising order (in the case of media) or a cut of profits (in the case of retail).

Rather than treating their readers and viewers as a product to be sold to advertisers via networks and exchanges, these publishers realize that they can develop products to sell their deeply engaged and loyal audiences — directly. Like a digital subscription to The New Yorker. Like paid access to Slate+ podcasts. Like M&A financial research from the FT for investing professionals. Like insider analysis on the beltway from Atlantic Media. And even direct commerce, most usually via affiliate relationships, as proven by The Wirecutter.

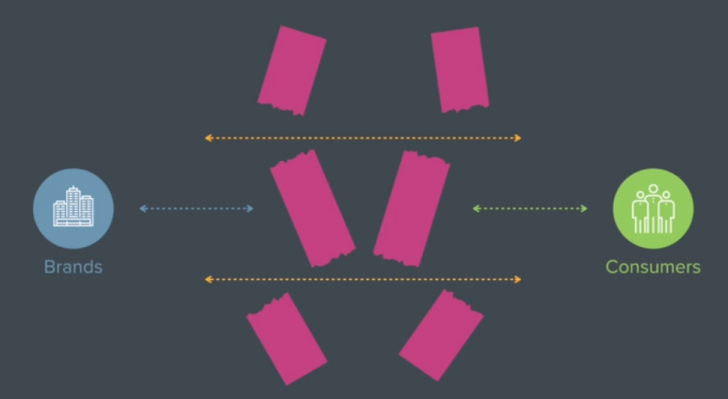

The other side of The Great Reckoning happens among brands. Rather than treating their consumers as mere cookie IDs to be targeted across the web, brands will directly build a digital relationship with their customers and prospects. To achieve this goal, they’ll need to do something they’re not used to doing: publishing lots of useful content on their own.

They will enlist the help of established professional publishers in this endeavor; see e.g. the NYT Brand Studio and Atlantic Media Strategies. But they will also completely redesign their owned-and-operated sites/apps to meet consumers where they are, rather than relying on the middle men of the broken attention economy.

Information is king

I want you to think about the biggest consumer purchase you make. Perhaps that’s your car; the decision of which vacation resort to visit; or, maybe, your laptop or mobile phone. Whether this purchase was $500 or $50,000, it was probably a big deal to you. It represented a chunk of your savings — hard-earned cash that you rightfully spent for your own benefit.

Now ask yourself this question: do you think what made the difference between you buying that product vs one of its competitors was a banner ad you saw on the web? Or a Facebook ad creeping on your profile? Or a Google ad for a keyword search you typed?

Even if you can imagine that one of those ads had an effect, I bet you would rather not admit it. You would rather imagine — as I would — that the reason you made that big purchase is because you wanted that product, or that you researched the best product on the market and made an informed purchasing decision.

Apple is a brand that understands this. That is why on their website, you’ll find luscious photographs of their products; interviews with the designers behind them; and detailed technical specifications. The Apple buyer doesn’t need to be tricked into buying the new iPhone — they wait in line for days to get the new release, after reading hundreds of anticipatory reviews online. And when Apple runs advertisements, they aren’t trying to persuade you to buy an Apple product. They are reminding you that you probably want to buy an Apple product. There’s a big difference.

After “The Great Reckoning,” brands can go direct to consumer with not just their products/services, but also with content. Rather than helping other brands buy their audience via adtech, publishers will help other brands to develop their own fans via content marketing and audience development techniques.

Brands that produce a regular drumbeat of content detailing their products and the thought that went into them will be well-positioned for The Great Reckoning.

No one wants to be tricked into buying a product. People want to make an informed purchase. If the consumer gets more information — even if it is occasionally biased — with which to make that purchasing decision, that consumer is better off. But most importantly, the consumer isn’t treated like a sucker. The consumer, is, instead, respected and empowered.

True brands rise above

In this scenario, going direct to consumer isn’t just about cutting out the adtech middlemen. It is, instead, about becoming a true brand. And this should be the aspiration of every brand on the web — because becoming a true brand means you have connected with consumers on a trustworthy foundation.

I think more consumer brands will aspire to Apple-level cultural relevance over time. I think more publishers will also do the same.

Many publishers already have this true brand status, and this, by definition, means they have an amazing target audience to which they can sell useful products. They don’t have to rely on the attention economy’s race-to-the-bottom — they can turn their readers and viewers into loyalists and fans. They can even turn them into customers.

Publishers will evolve to resemble the likes of The Financial Times, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and The WireCutter over time. That is, they will diversify their revenue base away from programmatic display advertising. This might even mean giving other brands — the ones who already have useful products to sell — some assistance in the strategy behind their direct-to-consumer marketing efforts, which might even include some premium advertising.

In The Great Reckoning, the three major actors in the ecosystem — consumers, brands, and publishers — all establish a much healthier foundation. Consumers pay publishers and brands for products they love, products that solve real problems for them. Brands compete in the marketplace of products and ideas, rather than solely communicating with dollars via ad impressions and clicks. And publishers establish direct relationships with both brands and consumers; rather than harvesting and delivering commodity consumer IDs and consumer time, they develop differentiated content with a real community.

The Great Reckoning will come

It’s not a matter of “if”, but “when”. The changes we can expect will be transformative:

- Publishers will diversify their revenue beyond programmatic advertising, thus developing a more monetizable relationship with their readers and viewers.

- Brands will realize that aside from Facebook and Google, the digital ad ecosystem is a mess. So, they will go direct-to-consumer with content and information.

- Digital marketing will be less about clicks and conversions. Instead, it will be about developing true brands, with aspirational examples being companies like Apple and The Financial Times.

- Publishers will stop banging their heads against the wall trying to monetize news in better ways — instead, they will focus on monetizing any products that their users view as uniquely valuable.

- Both sides will use the adtech industrial complex only insofar as it can generate some top-of-funnel traffic; otherwise, they will cut out the middlemen and establish direct relationships with their customers and fans.

- The web, as a whole, will be better off.

We should remember that the dream of the web was a free and open marketplace of products and ideas. The Great Reckoning is about a return to that important concept. Companies and consumers can finally take the web seriously. It’s no longer a side channel for products/services, or a second screen for attention. It’s now the primary channel for products/services, the main screen for attention.

Consumers today have choice, convenience, and freedom. But brands need to wise up to the power of direct audience development, or be left behind.

It’s a new day for the attention economy. May the best products and ideas win!

Image sources

- The graphs on ad spending come from this tweet with data on demand generation by Benedict Evans at a16z.

- The diagrams showing the wall between consumers and brands comes from the presentation “How Going Direct Changes Everything” by Jeff Jordan at a16z.

One thought on “The Great Reckoning in Digital Attention”